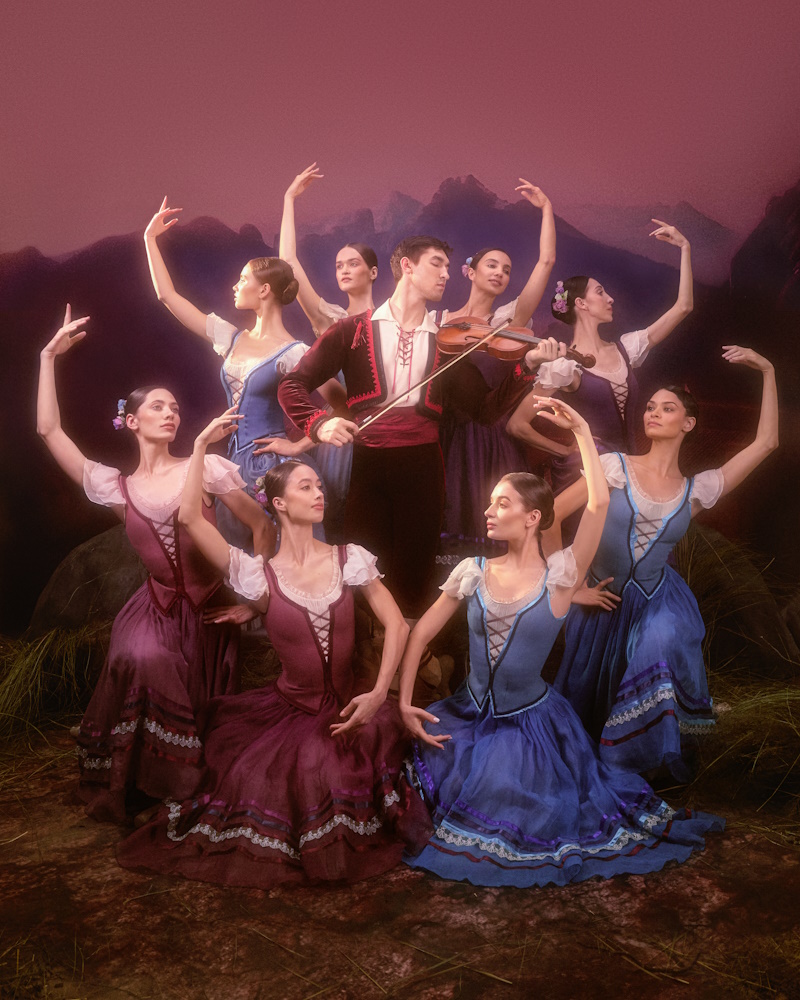

Laurencia

ballet in two acts

music by Alexander Krein

“Laurencia” is an extraordinarily spectacular performance, in which the emotional intensity and speed of the action are conveyed by a bright dance language. Classical steps in “Laurencia” are combined with fiery Spanish rhythms. Virtuoso solos and duets, harmonious ensembles, exciting crowd scenes help unfold a dramatic story based on the play by the Spanish playwright Lope de Vega “The Sheep Spring”.

Act one

Scene one

In the Spanish village of Fuente Ovejuna, all is merry animation as the villagers await the return of the Commander. As his campaign was a success, it is hoped that, contrary to his nature, the Commander will be kind and gracious. The villagers tease Laurencia and her sweetheart Frondoso. Laurencia also teases her ardent admirer. The violinist Mengo appears. Laurencia’s friend Pascuala asks him to play and get the young people dancing.

The Commander appears. The people give him a cautious welcome, but he does not pay much notice: his attention is drawn to the beautiful Laurencia. Ordering everyone to disperse, the Commander detains only her. Her friend Pascuala remains with her. Laurencia rejects the Commander’s advances. Annoyed, the Commander orders his soldiers to bring Laurencia and Pascuala to his castle, but the girls manage to escape.

Scene two

Frondoso reveals his feelings to Laurencia, but the capricious girl responds evasively. Suddenly the Commander appears before Laurencia and tries to kiss her. Frondoso fearlessly throws himself at the Commander, saving Laurencia from her hated admirer. The Commander vows revenge on both of them.

A group of girls come to the stream to wash clothes. They are more occupied with chatting than laundry, especially as Mengo also arrives. Jacinta runs in, chased by soldiers. Mengo defends Jacinta, but the soldiers knock him down. The Commander returns. Jacinta begs for his protection, but he hands her over to the soldiers. Laurencia, now convinced of Frondoso’s faithfulness, bravery and devotion, agrees to marry him.

Act two

Scene three

The whole village merrily celebrates Laurencia and Frondoso’s wedding. The merrymaking is interrupted when the Commander appears, looking sombre. He has come to take his revenge. He gives orders for Frondoso to be imprisoned and Laurencia to be taken to his castle. The people are horrified.

Scene four

At night, the men gather in the forest. They know they must fight the tyrant, but from fear and indecision they merely clench their fists and utter curses. Laurencia enters unsteadily, battered and with her dress torn, but her will is strong and she is filled with fury. She shames the men for their inaction and calls on them to rise up and fight. Her impassioned call fills their hearts with courage. All the village women support Laurencia.

Scene five

Armed with knives, scythes, clubs, and sticks, the people storm in the inner rooms of the castle. They free Frondoso from incarceration and set off to get even with the Commander. He tries to flee, but the peasants capture him. He offers them gold to let him go, but is met by an indignant refusal. The dead tyrant’s helmet set up on the pole symbolizes the victory of the people of Fuente Ovejuna.

Premiere of the production: 5 June 2010

Stage version after Lope de Vega’s play Fuente Ovejuna

Music revised for the Mikhailovsky Theatre

- ChoreographyVakhtang Chabukiani revised by Mikhail Messerer

- Stage and Costume DesignVadim Ryndin

- StagingMikhail Messerer

- Designers of the revivalOleg Molchanov (sets), Vyacheslav Okunev (costumes)

- Lighting DesignerMikhail Mekler

- VideoVadim Dulenko

- Musical Director of the productionValery Ovsyanikov

Sets and costumes produced at the Vozrozhdenie Theatrical Design Studios